Maria Tallchief

Osage

(dancer and teacher; Fairfax, Oklahoma)

"A ballerina takes steps given to her and makes them her own. Each individual brings something different to the same role,

As an American, I believe in great individualism. That's the way I was brought up." Maria Tallchief

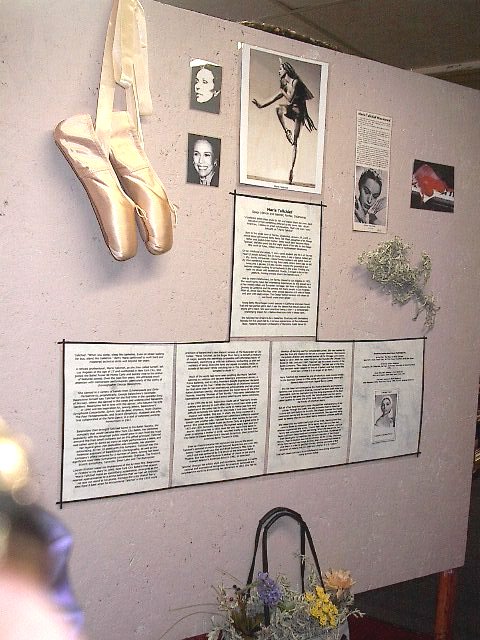

The physical museum's panel for Maria Tallchief

Born in the small town of Fairfax, Oklahoma, January 24, 1925.

a mixed-blood girl named Betty Marie Tallchief, daughter of an Osage father and Scotch-Irish mother. Betty much later became Maria Tallchief, and she spent the first eight years of her life on the Osage Hills north of Tulsa, Indian lands of northeastern Oklahoma.

Of her childhood she wrote, "I was a good student and fit in at Sacred Heart (Catholic School). But in many ways, I was a typical Indian girl -- shy, docile, introverted. I loved being outdoors and spent most of my time wandering around my big front yard, where there was an old swing and a garden. I'd also ramble around the grounds of our summer cottage hunting for arrowheads in the grass. Finding one made me shiver with excitement. Mostly, I longed to be in the pasture, running around where the horses were..."

Like so many Oklahomans, her family moved to Los Angeles in 1933. She would surely have had interesting experiences as she looked back at her mixed Indian and European heritage, her time in Oklahoma, her journey to California and life among the many people in Los Angeles. After all, those were the days when people became rich with oil fields and poor with dusty crops. The Osage Nation became rich when oil was found under their lands!

Young betty Marie began music lessons in California and soon found that she had perfect pitch. But it was the dance that would capture the young girl's heart. She soon practiced being a star -- a considerably challenging dream for a Native American child in those days.

She followed her dream to be a ballerina. Studying with Bronislava Nijinska for five years led to a nervous appearance at the Hollywood Bowl. Madame Nijinska's philosophy of discipline made sense to Tallchief. "When you sleep, sleep like ballerina. Even on street waiting for bus, stand like ballerina." Betty Marie continued to work hard and mastered technical skills well beyond her years.

A refined professional, Maria Tallchief, as she then called herself, left Los Angeles at the age of 17 and auditioned in New York City. She joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and quickly rose to the status of featured soloist. Over the next five years, she attracted much attention with memorable performances, particularly of the works of choreographer George Balanchine.

She danced in a variety of ballets from Scheherezade and Gaite Parisienne to, prophetically, George Balanchine's Serenade. Balanchine himself saw Tallchief for the first time in the operetta Song of Norway, where she danced in the corps and understudied Alexandra Danilova. Balanchine fell in love with the dancer, who became his wife in 1946 and the inspiration for, among others, Balanchine's Symphonie Concertante, Sylvia: pas de deux, Orpheus, Night Shadow, The Four Temperaments, and Scotch Symphony. Husband and wife first collaborated at the Paris Opera, in a sort of extended working honeymoon in 1947.

Balanchine then brought Tallchief home to his Ballet Society, the company that would become New York City Ballet. Her immense popularity with the American public would grow in part from the huge demand the then small company put on this gifted principal: Tallchief was called upon to dance as many as eight performances a week, and her legend grew. Her dedication was complete, her abandon astounding. In her 18 years with this company, Tallchief was the foremost exponent of Balanchine's choreography, as well as the company's prima ballerina for a number of years. Among her most significant roles were Symphomie concatenate, Orpheus, The Firebird, Scotch Symphony, Caracole, Swan Lake and The Nutcracker.

Lincoln Kirstein noted his impressions of the by then Mrs. Balanchine in Firebird in his diary in 1949, New York City Ballet's first season. "Maria Tallchief made an electrifying appearance, emerging as the nearest approximation to a prima ballerina that we had yet enjoyed." He was not alone in his praise. Perhaps the critic Walter Terry described it best when he encountered Tallchief in the 1954 world premiere of Balanchine's now historic version of The Nutcracker at City Center. "Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being. Does she have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland? While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it."

Much of the world had never seen anything like Maria Tallchief. Admired by millions, she became America's preeminent dancer, a Prima Ballerina, and in 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower declared her "Woman of the Year." When the Governor of Oklahoma honored her that same year for her international achievements and her proud Native American identity, she was given the honor name of Wa-Xthe-Thomba, meaning "Woman of Two Worlds." This name celebrates her international achievements as a prima ballerina and Native American.

In the 1955 Pas de Six, Balanchine made use of Tallchief's innate subtlety and delicacy to such effect that it would take other great ballerinas in the same role for the world to realize just how very difficult technically this ballet is: She made it look easy, natural, musical and radiant. She was, in short, the living essence of a Balanchine ballet. Yet when Balanchine's attentions shifted to another dancer--and another wife--Tallchief found other outlets for her own genius. She joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo as a guest artist in 1955 and 1956, famously receiving the highest salary ever paid any dancer. She remarried in 1956, took her only leave from ballet in order to become a mother in 1958, returned briefly to the New York City Ballet to create Balanchine's Gounod Symphony, then joined the American Ballet Theatre in 1960.

Even as Firebird became her signature role around the world, Tallchief's personal triumphs ranged beyond Balanchine and even into Antony Tudor's Jardin aux lilas and Birgit Cullberg's Miss Julie, in which she was partnered by Erik Bruhn at the American Ballet Theatre. She was Rudolf Nureyev's partner of choice in the young Russian defector's American debut in 1962, on television.

Tallchief, through her artistic style and excellence, continued to inspire national and international recognition for American balletuntil she surprised the world by announcing her retirement in 1965. She had no intention of dancing past her considerable prime. She now wanted to pass her love and respect for her art to younger dancers. She became the artistic director and beloved teacher of the Chicago Lyric Opera Ballet in 1975; With her sister Marjorie, she founded the Chicago City Ballet in 1981 and until 1987, Tallchief was the artistic director of the Ballet Company. "New ideas are essential," Tallchief said at the time, "but we must retain respect for the art of ballet--and that means the artist too--or else it is no longer an art form."

Maria Tallchief was honored as one of America's most revered artists by the Kennedy Center in 1996, along with prize-winning playwright Edward Albee and music legend Benny Carter.

. She has been acknowledged as the most technically accomplished ballerina ever produced in America, Tallchief has been both muse and instrument, both the inspiration and the living expression of the best our country has given the world. Her individualism and her genius came together to create one of the most vital and beautiful chapters in the history of American dance.

But all of her fame and glory never changed her understanding of her culture. Through the years, she also promoted Native American culture and contributions to the arts. She always admired the Osage ceremonial dances and the ways of her ancestors. She reported being upset by teasing that she and other Native American children suffered.

She researched the history and origin of her tribe, learning how they came to reside in Oklahoma. Of the terror her tribe and her own relatives experienced she wrote, "Cousin Pearl was an orphan, and our family was concerned for her well-being. When she was small, her house had been firebombed and everyone inside killed, murdered for their headrights (oil royalties paid to each member of the Osage Nation). Pearl's situation was not uncommon. In the 1920s, villainous White men married into Osage families, then poisoned their wives or shot them in order to get their money, another example of the slaughter of Indians that is a notorious chapter of U.S. history."

Tallchief's ideals and many accomplishments have strong influence on young scholars today.

Read the books about Maria Tallchiefs life

Additional Resources:Maynard, Olga. Bird of Fire: The Story of Maria Tallchief. New York: Dodd, Mead 1961. NOTES: Covers Tallchief's youth and career.

Livingston, Lili Cockerville. American Indian Ballerinas Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

With Larry Kaplan. Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

With Rosemary Wells. Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina New York: Viking, 1999. NOTES: Juvenile literature.