|

Ancient

Voices

A

Museum to honor the least known people in North America,

the Original Tribal Women |

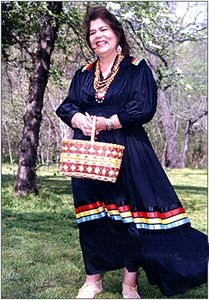

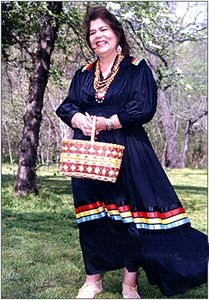

CHIEF WILMA MANKILLER

Cherokee

1945 -

The first woman Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

"Women in leadership roles can help restore balance and wholeness to our communities."

Wilma Pearl Mankiller (Cherokee military term for a village protector) was born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma on November 18, 1945. She came from a large family that spent many years on the family farm in Oklahoma. Mankiller grew up on her father Charley's ancestral Oklahoma lands. "Dirt poor" was how she described her early life. The Mankillers frequently ate suppers of squirrel and other game. The house had no electricity. Her parents used coal oil for illumination. However Wilma said later, "As far back as I can remember there were always books around our house. This love of reading came from the traditional Cherokee passion for telling and listening to stories. But it also came from my parents, particularly my father.... A love for books and reading was one of the best gifts he ever gave his children."

Unfortunately, a poor local economy made the Mankiller family an easy target for the Bureau of Indian Affairs relocation program of the 1950s. Government agents were entrusted with the job of moving rural Cherokees to cities, effectively dispersing them and allowing others to buy their traditional, oil-rich lands. In 1959 the family moved to San Francisco, where Wilma's father could get a job and where Wilma began her junior high school years. Her father Charley found work as a rope maker and the family settled down. Wilma had a difficult transition. She and her siblings were the proverbial hicks in the big city. This was not a happy time for her. She missed the farm and she hated the school where white kids teased her about being Native American and about her name. A kindly Mexican family showed them how to work a telephone and taught Wilma to roller skate. Charley Mankiller had instilled in his children a pride in their heritage, and San Francisco's Indian Center, located in the Mission District, fostered it.

Mankiller decided to leave her parents and go to live with her maternal grandmother, Pearl Sitton, on a family ranch inland from San Francisco. The year she spent there restored her confidence and after returning to the Bay Area, she got increasingly involved with the world of the San Francisco Indian Center. "There was something at the Center for everyone. It was a safe place to go, even if we only wanted to hang out." The Center provided entertainment, social and cultural activities for youth, as well as a place for adults to hold powwows and discuss matters of importance with other BIA relocatees. Here, Mankiller became politicized at the same time reinforcing her identity as a Cherokee and her attachments to the Cherokee people, their history and traditions The center became Wilma's after-school refuge.

Mankiller exhibited no appetite for intellectual ambition as a teenager. In her 1993 autobiography, "Mankiller: A Chief and Her People," co-written with Michael Wallis, she recalled hating the classroom. When she graduated from high school in June 1963, she expected that to be the end of formal schooling. "There were never plans for me to go to college," she said. "That thought never even entered my head."

Instead, a tedious pink-collar job followed graduation, as did a fast courtship and marriage to a handsome Ecuadorean college student, Hugo Olaya, with whom Mankiller had two children. Olaya's family was middle-class; his prospects were good. At 17 the pretty girl, whose dark, flashing eyes gave her a resemblance to actress Natalie Wood, settled down to live the life of a California house-wife -- replete with psychedelic pantsuits, baby strollers and European vacations.

San Francisco transformed many people living there during the 1960s. Its shabby, lunch-pail-toting neighborhoods became crucibles for a society recasting its values. The fire eventually caught a shy housewife and mother in her 20s named Mrs. Hugo Olaya and alchemized her into Wilma Pearl Mankiller, a symbol of both feminism and Native American self-determination.

When a group of Native Americans occupied Alcatraz Island in November 1969, in protest of U.S. Government policies, which had, for hundreds of years, deprived them of their lands, Mankiller participated in her first major political action.

"It changed me forever," she wrote. "It was on Alcatraz...where at long last some Native Americans, including me, truly began to regain our balance."

In the years that followed the "occupation," Mankiller became more active in developing the cultural resources of the Native American community. She helped build a school and an Indian Adult Education Center. She directed the Native American Youth Center in East Oakland, coordinating field trips to tribal functions, hosting music concerts, and giving kids a place to do their homework or just connect with each other. The youth center also gave her the opportunity to pull together Native American adults from around Oakland as volunteers, thus strengthening their ties.

In San Francisco, she learned about the women's movement and organizing. Mankiller says she learned on the job, joking "my enthusiasm seemed to make up for my lack of skills." But she was, in truth, a natural leader.

She returned to Oklahoma in the 1970s where she worked at the Urban Indian Resource Center and volunteered in the community. In 1981 she founded and then became director of the Cherokee Community Development Department, where she orchestrated a community-based renovation of the water system and was instrumental in lifting an entire town, Bell, Oklahoma, out of squalor and despair.

"One of the things my parents taught me, and I'll always be grateful for the gift, is to not ever let anybody else define me."

It wasn't until 1970 that Washington allowed the Cherokee tribe to elect its leaders directly. In 1983, Wilma Mankiller ran for Deputy Chief of the Cherokee Nation. The campaign was not an easy one. Initially, she faced much opposition, much of which was the result of sexism.

There had never been a woman leader of a Native American tribe. She had many ideas to present and debate, but encountered discouraging opposition from men who refused to talk about anything but the fact that she was a woman. Her campaign days were troubled by death threats, and her tires were slashed. She sought the advice of friends for ways to approach the constant insults, finally settling on a philosophy summed up by the epithet, "Don't ever argue with a fool, because someone walking by and observing you can't tell which one is the fool." In the end, Mankiller had her day: she was elected as first woman Deputy Chief, and over time her wise, strong leadership vindicated her supporters and proved her detractors wrong.

In 1985, when Chief Ross Swimmer resigned to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., Mankiller was obligated to step into his position. In 1987, after a landslide victory, Mankiller became the first freely-elected Chief of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Also becoming the first woman to serve as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Mankiller was again elected Chief in 1991, but poor health forced her to retire from that position in 1995.

Mankiller brought about important strides for the Cherokees, including improved health care, education, utilities management and tribal government she made them tribal priorities. She raised $20 million to build a much-needed infrastructure for schools and other projects, including an $8 million job-training center. The largest Cherokee health clinic was started under her tenure in Stilwell, Okla., and is now named in her honor. Mankiller also sought to reunite the Eastern Cherokee, a group based in North Carolina, with the larger Western division. She wanted to attract higher-paying industry to the area, improving adult literacy, supporting women returning to school and more. However, Mankiller also lived in the larger world, and was active in civil rights matters, lobbying the federal government and supporting women's activities and issues. She said: "We've had daunting problems in many critical areas, but I believe in the old Cherokee injunction to 'be of a good mind.' Today it's called positive thinking."

As the leader of the Cherokee people she represented the second largest tribe in the United States, (the largest being the Dine (Navajo) Tribe) - she was responsible for 139,000 people and a $69 million budget. She was the first female in modern history to lead a major Native American tribe and has become known not only for her community leadership but also for her spiritual presence. A visionary Wilma Mankiller continues to be a political, cultural, and spiritual leader in her community and throughout the United States.

As a people, the Cherokee are highly proud of Wilma, who remains perhaps the most celebrated Cherokee of the twentieth century. "Prior to my election," says Mankiller, "young Cherokee girls would never have thought that they might grow up and become chief."

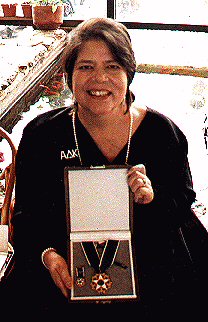

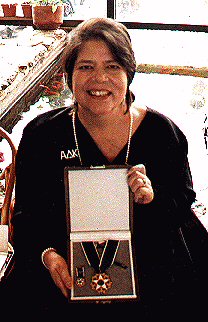

Honors and the Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipient

In 1990 Oklahoma State University honored her with the Henry G. Bennett Distinguished Service Award, and in 1993 she was Inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame, Seneca Falls, NY

In 1998, President Clinton awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

She is pictured at a reception held in her honor at the Cherokee Heritage Center on Sunday, January 18, 1998. Approximately 300 people attended the reception.

Photo by David Cornsilk

|

Her journey -- from complacency to activism to political power -- followed a familiar boomer flight path, but hers was a working woman's ascendancy.

I personally met Wilma Mankiller during the 80's in New Jersey, I found her to be very open, friendly and smart. She was presenting a talk and I was lucky enough to get tickets. She spoke to those who wanted to ask questions afterwards and I was one of those people. She didn't hurry us off or rush away, she patiently waited until all the questions were asked and answered before very humbly thanking us for coming to see her. She then left. I thought at the time what a great leader she was, and how lucky the Cherokee people were to have someone like her as their Chief. She cared and would do what she needed to do to allow them to have the things that were their right. She gained my respect that evening, and so when I decided to make this museum I knew that she would be one of the Exceptional Women that would be featured here. - Gloria

RECOMMENDED READING

|

|

|

|

|

Wilma Mankiller

by Linda Lowery

Grades 2-4-

A competent, easy-to-read biography of the first woman chief of the Cherokee Nation

|

|

Wilma Mankiller: Leader of the Cherokee Nation

by Della A. Yannuzzi

Grade 6-9? As a highly successful chief and as the first contemporary female Indian leader to achieve her status, Mankiller has become a role model for many young people. |

Research Resources

Susannah Abbey & Andrew Nelson

Harris, Jo D. A Brief Interview with Chief Mankiller. Lewiston, Idaho: Confluence Press in association with Women's Action Committee, Lewis-Clark State College, 1996.

Mink, Gwendolyn, Marysa Navarro, and Gloria Steinem, editors. The Reader's Campanion to U.S. Women's History. Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998.

Yannuzzie, Della A. Wilma Mankiller: Leader of the Cherokee Nation. Hillside, New Jersey: Enslow Publishers, 1994.

Editor with Vine Deloria, Barbara Deloria, Kristen Foehner, and Sam Scinta. Spirit & Reason: The Vine Deloria, Jr., Reader. Fulcrum Pub., 1999.

With Michael Wallis (contributor). Mankiller: a Chief and her People. St. Martin's Press, 1994.

|