|

In

1862 bounties were placed on the scalps of Dakota

people by Governor Alexander Ramsey which

eventually reached $200

|

History

On

November 7, 2014, as in every second year since

2002, Dakota people from the United States and

Canada will begin a 150-mile long Commemorative March

through southern Minnesota in honor of their ancestors

who were forcibly removed from the Lower Sioux Agency

to concentration camps at Mankato and Fort Snelling

in November of 1862. For the Dakota this commemoration

signifies an opportunity to remember and grieve for

the suffering endured by their ancestors as well as

to relate a perspective of the event which has rarely

been told.

On November 7, 1862, a group of about

1,700 Dakota, primarily women, children and elderly,

were force-marched in a four-mile long procession from

the Lower Sioux Agency to a concentration camp at Fort

Snelling. Two days later, after being tried and convicted,

over 300 condemned men who were awaiting news of their

execution were placed in wagons while they were shackled

and then transported to a concentration camp in Mankato,

Minnesota.

Both

groups had surrendered to the United States army at

the end of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, believing they

would be treated humanely as prisoners of war. Instead,

the men were separated out and tried as war criminals

by a five-man military tribunal. As many as forty cases

were tried in a single day, some taking as little as

five minutes. Upon completion of the trials, 307 men

were condemned to death and 16 were given prison sentences.

The remaining Dakota people, primarily women, children,

and elderly were then forced to endure brutal conditions

as they were forcibly marched to Fort Snelling and then

imprisoned in Minnesota's first concentration camp through

a difficult winter.

As

both groups were paraded through Minnesota towns on

their way to the camps, white citizens of Minnesota

lined the streets to taunt and assault the defenseless

Dakota. Poignant and painful oral historical accounts

detail the abuses suffered by Dakota people on these

journeys. In addition to suffering cold, hunger, and

sickness, the Dakota also endured having rotten food,

rocks, sticks and even boiling water thrown at them.

An unknown number of men, women and children died along

the way from beatings and other assaults perpetrated

by both soldiery and citizens. Dakota people of today

still do not know what became of their bodies.

After

38 of the condemned men were hanged the day after Christmas

in 1862 in what remains the largest mass hanging in

United States history, the other prisoners continued

to suffer in the concentration camps through the winter

of 1862-63. In late April of 1863 the remaining condemned

men, along with the survivors of the Fort Snelling concentration

camp, were forcibly removed from their beloved homeland

in May of 1863. They were placed on boats which transported

the men from Mankato to Davenport, Iowa where they were

imprisoned for an additional three years. Those from

Fort Snelling were shipped down the Mississippi River

to St. Louis and then up the Missouri River to the Crow

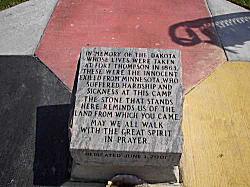

Creek Reservation in South Dakota. A memorial to some

of those people was dedicated at Crow Creek in 2001.

The

memorial at Crow Creek

This

ethnic cleansing of Dakota people from Minnesota was

one part of the fulfillment of a larger policy of genocide.

Governor Alexander Ramsey had declared on September

9, 1862 that "The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be

exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of

the state." The treatment of Dakota people, including

the hanging in Mankato and the forced removal of Dakota

people from Minnesota, were the first phases of Ramsey's

plan. His plan was further implemented when bounties

were placed on the scalps of Dakota people which eventually

reached $200. Punitive expeditions were then sent out

over the next few years to hunt down those Dakota who

had not surrendered and to ensure they would not return.

These actions cleared the way for white settlement of

Minnesota.

While

small numbers of Dakota people began trickling back

to their homeland by the late 1880s, most Dakota people

remain in exile from their ancient homeland. This Commemorative

March is a reason for Dakota people to not only honor

their ancestors by acknowledging the suffering they

endured, it is also a chance to tell the truth about

Minnesota's shameful ethnic cleansing of its Indigenous

people and an opportunity for Dakota reconciliation

in their homeland of Minnesota Makoce (Land Where the

Waters Reflect the Skies) 140 years later.

In

2002 Ron Leith who is the carrier of the Eagle staff

for the 38 hanged at Mankato helped with our opening

ceremonies. He asked Gerald Standing who is from the

Wahpeton Reserve in Saskatchewan, to take care of the

staff for the march, so Gerald started them out every

morning carrying the eagle staff and ended with it every

day. Gerald put in a lot of miles on the march, walking

every day even when it was very painful. The picture

below was taken on the first morning of the march as

they were leaving Lower Sioux.

The

marchers leaving the Lower Sioux in 2002

Leo

Omani, from the Wahpeton Reserve in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

was with the group for the entire march and it was his

little red car that served them as the lead car for

us the entire way (he and Gerald Standing took turns

driving it). Leo was also the person who conceived of

the idea for a commemorative event to honor the group

of primarily women and children who made the march in

1862. The picture below is of him taken the morning

they left Lower Sioux on the first day.

Leo

Omani