Dakota Commemorative March 2014

|

She

was going to put her mother in the wagon, but it was gone. They

stood there not knowing what to do. She wanted to put her mother

someplace where she could be warm, but before they could get away,

the soldier came again and stabbed her mother with a saber.

|

|

||

|

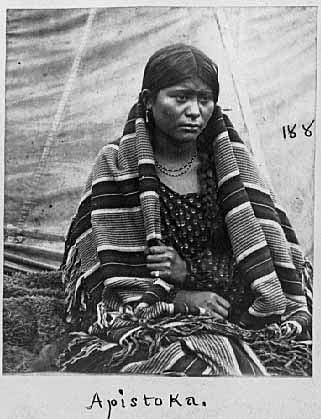

Apistoka

A young Dakota woman who held the pain of a Nation in her eyes. |

|

Eye Witness

Report from Maza

Okiye Win (Isabel

Roberts) in 1862 as told to and carried

by Elsie Cavender. I first learned of this forced relocation from my grandmother, Elsie Cavender, who carried a narrative account passed down to her from her grandmother, Maza Okiye Win (Woman Who Talks to Iron). Maza Okiye Win was ten years old at the time of the war and thus the accounts of events she relayed to her children and grandchildren were born of her own traumatic hardships. Kunsi (Grandmother) Elsie entitled this story of her grandmother's "Death March," consciously drawing a parallel between this forced march and that of the Bataan Death March during World War II during which 70,000 American and Filipino soldiers were forced to walk a 63-mile journey to a prison camp while facing starvation and poor treatment. Learning of this event from a relative of ours who had experienced it, she saw similarities with the march her grandmother was forced to endure. The following account, which I recorded in 1990 with my grandmother remains the most descriptive and lengthy one yet documented. It is relayed here in my grandmother's words: "Right after the 1862 Conflict, most of the Sioux people were driven out of Minnesota. A lot of our people left to other states. This must have been heartbreaking for them, as this valley had always been their home. My grandmother, Isabel Roberts (Maza Okiye Win is her Indian name), and her family were taken as captives down to Fort Snelling. On the way most of them [the people] walked, but some of the older ones and the children rode in a cart. In Indian the cart was called canpahmihma kawitkotkoka. That means crazy cart in Indian. The reason they called the cart that is because it had one big wheel that didn't have any spokes. It was just one big round board. When they went they didn't grease it just right so it squeaked. You could just hear that noise about a mile away. The poor men, women, old people, and children who had to listen to it got sick from it. They would get headaches real bad. It carried the old people and the children so they wouldn't have to walk. Most of the people just walked. Some of them if they were lucky rode horses. They passed through a lot of towns and they went through some where the people were real hostile to them. They would throw rocks, cans, sticks, and everything they could think of: potatoes, even rotten tomatoes and eggs. They were throwing these things at them, but the Indians still had to walk through the main streets. So they had to take all that. Then when they would pass through the town they would be all right. A lot of those towns I don't know the names of in English. They used to say them in Indian. The two towns that were the worst they had to got through were Henderson and New Ulm, Minnesota. I didn't know the name in English so I said, "Grandfather, do you know how they call them in English?" "No, I just know their Indian names," he said. So then I had to go to Mr. Fred Pearsall. In Indian his name was Wanbdi Ska (White Eagle). He was a white man, but he knew a lot of things about the conflict. He talked Indian just like we do. He knew all those things that happened and he knew just what words to use to describe the times. So I was able to get the names of those towns. They were the worst ones they had to go through. When they came through New Ulm they threw cans, potatoes, and sticks. They went on through the town anyway. The old people were in the cart. They were coming to the end of the town and they thought they were out of trouble. Then there was a big building at the end of the street. The windows were open. Someone threw hot, scalding water on them. The children were all burned and the old people too. As soon as they started to rub their arms the skin just peeled off. Their faces were like that, too. The children were all crying, even the old ladies started to cry, too. It was so hard it really hurt them but they went on. They would camp some place at night. They would feed them, giving them meat, potatoes, or bread. But they brought the bread in on big lumber wagons with no wrapping on them. They would just throw it on the ground. They would have them sleep in either cabins or tents. When they saw the wagons coming they would come out of there. They had to eat food like that. So, they would just brush off the dust and eat it that way. The meat was the same way. They had to wash it and eat it. A lot of them got sick. They would get dysentery and diarrhea and some had cases of whooping cough and small pox. This went on for several days. A lot of them were complaining that they drank the water and got sick. It was just like a nightmare going on this trip. It was on this trip that my maternal grandmother's grandmother was killed by white soldiers. My grandmother, Maza Okiye Win, was ten years old at the time and she remembers everything that happened on this journey. The killing took place when they came to a bridge that had no guard rails. The horses or stock were getting restless and were very thirsty. So, when they saw water they wanted to get down to the water right away, and they couldn't hold them still. So, the women and children all got out, including my grandmother, her mother, and her grandmother. When all this commotion started the soldiers came running to the scene and demanded to know what was wrong. But most of them [the Dakota] couldn't speak English and so couldn't talk. This irritated them and right away they wanted to get rough and tried to push my grandmother's mother and her grandmother off the bridge, but they only succeeded in pushing the older one off and she fell in the water. Her daughter ran down and got her out and she was all wet, so she took her shawl off and put it around her. After this they both got back up on the bridge with the help of the others who were waiting there, including the small daughter, Maza Okiye Win. She was going to put her mother in the wagon, but it was gone. They stood there not knowing what to do. She wanted to put her mother someplace where she could be warm, but before they could get away, the soldier came again and stabbed her mother with a saber. She screamed and hollered in pain, so she [her daughter] stooped down to help her. But her mother said, "Please daughter, go. Don't mind me. Take your daughter and go before they do the same thing to you. I'm done for anyway. If they kill you the children will have no one." Though she was in pain and dying she was still concerned about her daughter and little granddaughter who was standing their and witnessed all this. The daughter left her mother there at the mercy of the soldiers, as she knew she had a responsibility as a mother to take care of her small daughter.

"Up to today we don't even know where my grandmother's body

is. If only they had given the body back to us we could have

given her a decent funeral," Grandma said. So, at night, Grandma's

mother had gone back to the bridge where her mother had fallen.

She went there but there was no body. There was blood all over

the bridge but the body was gone. She went down to the bank.

She walked up and down the bank. She even waded across to see

if she could see anything on the other side, but no body, nothing.

So she came back up. She went on from there not knowing what

happened to her or what they did with the body. So she really

felt bad about it. When we were small Grandma used to talk about

it. She used to cry. We used to cry with her. " (published in Waziyatawin, "Grandmother to Grandaughter: Generations of Oral Tradition in a Dakota Family," in Devon Mihesuah, ed., Natives and Academics: Researching and Writing about American Indians) Copyright

of this report belongs to Waziyatawin

|