Dakota Commemorative March 2014

|

I

had walked in the path of these ancestors, my feet had retraced

the path of their suffering, and in that moment I felt their grief

and the grief of all the subsequent generations.

|

|

||

|

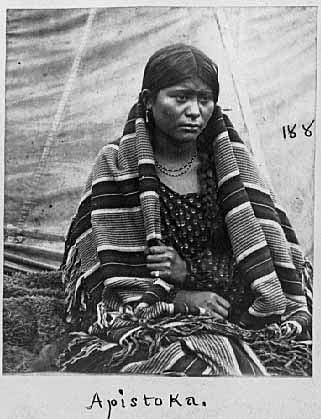

Apistoka

A young Dakota woman who held the pain of a Nation in her eyes. |

|

Reports of Experiences of the 2002 Commemorative March 'Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan (co-coordinator for the march) with her mother, Yvonne Wynde, arrived at Lower Sioux the night before the march began with a large bundle of wooden lathes, each one tied with a red strip of cloth and inscribed with two names, one on each side. The names represented the heads of families on the march and then imprisoned at Fort Snelling. Because the march to Fort Snelling was primarily composed of women, most of the names were those of women. In all there were about 300 such names, so two were written on each stake and a stake would be placed about every mile for the 150 miles between Lower Sioux and Fort Snelling. Yvonne had donated the stakes and cloth and Gaby worked with the children at Tiospa Zina Tribal School in Sisseton to tie the cloth and write the names on the stakes. Gaby commented later about the experience of watching these innocent children taking on the morose task of writing the names of those who suffered tremendous hardship and cruelty in 1862, but doing so happily, bringing a lightness and innocence to the project. Gaby and Yvonne brought half of the stakes to us that night at Lower Sioux and said they'd bring the other half as soon as they were ready and they could get them to us... Each mile offered a focused opportunity for us to collectively stop and remember those who suffered through the forced march in 1862. When the lead car stopped, either Deksi Leo or Ic'esi Gerald would pull out one of the stakes from the bundle in their car and all of us would gather around. A speaker of our language would read aloud the name to everyone present. Then one of the women present would hold the stake as it was pounded into the ground and offer the first prayer with tobacco. Everyone else could then come forward to offer their tobacco and prayers. In many ways this pounding of each stake into the ground was also about reclamation. Mile by mile we were physically reclaiming our memory, our history, and our land. We were also leaving a visible symbol of this reclamation. Some of the stakes lasted for months, marking our route of suffering and hardship, and a few are still standing today. The red strips of cloth on the stakes, waving in the wind, were important signifiers of the blood that was shed in 1862, but also the blood in the life that still breathes, our breath as descendants of those who made this original painful journey. The planting of the stakes was always a moving experience, but it was particularly moving those times when descendants were there to recognize their family names. I had originally learned about this march through my grandmother's oral historical account provided earlier in this volume. Her grandmother, Maza Okiye Win (Woman Who Talks to Iron), whom I have written about elsewhere was ten years old on the journey and carried vivid memories of the experience. Because I had so frequently heard her name and her stories, I fully expected at some time on the march to see her name on one of the stakes. I was not prepared for what I did see. Just a few miles outside of New Ulm, my uncle pulled out a stake from the car with the name Haza Win (Blueberry Woman) and I was startled as I realized this was my relative, this was Maza Okiye Win's mother. My sister, Audrey Fuller, had just formally had this family name passed on to her in a name-giving ceremony the previous summer. My uncle and I put the stake in and said the first prayers, but as I stood up with my hands still on the stake a flood of grief washed over me and I began to sob. I had walked in the path of these ancestors, my feet had retraced the path of their suffering, and in that moment I felt their grief and the grief of all the subsequent generations. Later when I gave it more thought, it made perfect sense that I would see Haza Win's name instead of Mazo Okiye Win's, as Haza Win would have been the head of the household at that time, especially after losing her own mother on the journey. That was one of the lucid moments on the journey when I felt the significance of our undertaking personally and powerfully. That was the second day of the march. ' Angela Cavender Wilson Copyright

of this report belongs to Angela Cavender Wilson

'As I got into my car, I saw a brave sight. There they were, I saw three adults and six children walking energetically and determinedly to the next town, New Ulm, with the eagle-staff leading the way. With tears in my eyes, I went through a mix of emotions. An initial reaction was anger, "where in the hell were our marchers?" We had about three dozen marchers the day before. That anger quickly dissipated. Then, my feelings turned to determination and pride. My thinking was, "well, if this is all who are going to be marching, then so be it. We'll do it!" Then, my thoughts turned to pride. There was my daughter, Dr. Angela Cavender Wilson, with her three children, my grandchildren! There was my niece, Ms. Marisa Pigeon, with two of her children and her niece! There was my tahansi ("cousin, male to male") from Canada, Leo Omani, who was carrying the eagle-feather staff (our toska, "nephew," Gerald Standing, was driving the little red car, our lead car). They were bravely walking down highway 14, in spite of their few numbers. I thought of how the 1,700 Dakota people back in 1862 were primarily women and children. ' One of the greatest spiritual gifts the marchers received was the approval and presence of the spirits, the presence of our grandfathers and the grandmothers! Several individuals, including Art Owen, one of our spiritual leaders from the Prairie Island Dakota Community, mentioned that they saw blue lights over the marchers as they approached the concentration camp at Ft. Snelling. The spirits of the 1,700 Dakota women, children, and elders were saying to the marchers "thank-you" for your remembering and honoring us, "thank-you" for your physical sacrifice. There were several marchers who marched the whole way, 150 miles, and were there every day of the march. Various marchers have indicated that this march will be done several times, beginning in 2004, and held either every year or every other year right up to 2012, the 150th anniversary of the Dakota-U.S. War of 1862. To reiterate, this was one of the best things I have ever done in my life. I feel closely to the marchers, those who were there every day or for most of the days. I have a debt of gratitude and feel closely to all those who helped to feed, who provided lodging, who gave of their own personal finances so that the marchers could have sandwiches, cookies, fruit, water. etc., and to all those who helped in their own unique ways to remember and honor the 1,700 Dakota people and to thank the Creator! Manipi kin hena wicunkiksuyapi! "We remember those who walked!" Chris Mato Nunpa Copyright of this report belongs to Chris Mato Nunpa Please

click through to the next page of reports on the 2002 march

here.

|