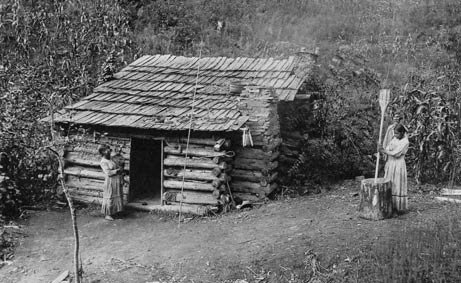

Cherokee Cherokee society was organized through seven mother-descent clans. It was through the mother that children gained identity, which afforded them citizenship. Meeting in a seven-sided structure, both men and women participated in the general council. Principal Chiefs were elected, and the Beloved Woman was speaker for the Women's Council. As the number of European settlers increased, many Cherokee inter-married with them, adopting and adapting to European customs, including the disenfranchisement of women. Gradually, the people as a whole turned to an agricultural economy while being pressured to give up traditional homelands. Cherokee Cabin

Photograph by James Mooney, courtesy National Anthropological Archives. The Trail of Tears or The Trail where the Women Cried 'Nunna daul Tsuny'

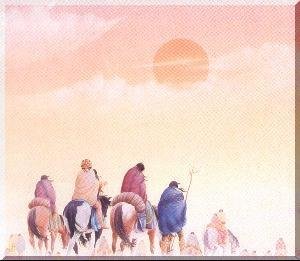

The painting above shows one southeastern tribe's journey west. Guarded by soldiers, Cherokee Indians carry their belongings in wagons and on their backs. During the 1830's more than 10,000 Cherokees were forced to make this long journey. Their journey is known as "The Trail of Tears."

By November 12, 1838, groups of 1,000 began the 800 mile overland march to the west. The last party, including Chief Ross, went by water. Now, heavy autumn rains and hundreds of wagons on the muddy route made roads impassable; little grazing and game could be found to supplement government rations. Two-thirds of the ill-equipped Cherokee were trapped between the ice-bound Ohio and Mississippi Rivers during January, 1839. On March 24, 1839, the last detachments arrived in the west. Some of them had left their homeland on September 20, 1838. No one knows exactly how many died during the journey. Missionary doctor Elizur Butler, who accompanied one of the detachments, estimated that nearly one fifth of the Cherokee population died. The trip was especially hard on infants, children, and the elderly. An unknown number of slaves also died on the Trail of Tears. The U.S. government never paid the $5 million promised to the Cherokees in the Treaty of New Echota. Oklahoman (April 7, 1929), cited in Ehle, The Trail of Tears, 358. The Cherokee people have very few stories of what happened during the removal, the older people who endured it wouldn't talk about it because it was too painful. That's very unusual. Here though I am adding a couple of stories I have found from the survivors of the relocation.

A full blood survivor of the march remembered that although suffering from a cold, Quatie Ross, the wife of Chief John Ross, gave her only blanket to a child. Mrs. Ross became sick and died of pneumonia at Little Rock.

In 1972, Robert K. Thomas, a professor of anthropology from the University of Chicago and an elder in the Cherokee tribe, told the following story to a few friends:

Dig Adds to Cherokee "Trail of Tears" History

January 23, 2006

Archaeologists working in the rugged mountains of southwestern North Carolina are adding new details to the story of a tragedy that took place more than 160 years ago. The scientists are uncovering the remains of farms and homes belonging to the Cherokee Indians before they were forced to abandon their property and move to Oklahoma. About 16,000 Cherokee and hundreds of other Native Americans were forced out of North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama in the late 1830s. The event came to be known among the Cherokee as the Trail of Tears. Brett Riggs, an archaeologist with the University of North Carolina's Research Laboratories of Archaeology, is leading the excavations. He said the relocation of the Indians was a form of ethnic cleansing. "A group of people in possession of sovereign territory with a sovereign government were forced to abandon that land, and were forcibly deported," Riggs said. "They were detained by the U.S. military, and then moved away from their homes to open the area for settlement by a whole different population. That fits the bill for describing ethnic cleansing as well as anything I can think of." Everyday Life Riggs and his crew of UNC archaeologists are working about 90 miles (145 kilometers) southwest of Asheville. They're uncovering remnants of the Cherokee's lives before they were rounded up and moved west. "What we're finding in the ground is the stuff of everyday life—refuse, people's trash," Riggs said. "In terms of documenting the Trail, this confirms that these particular sites were associated with Cherokee families." The archaeologists have recovered pieces of pottery and china, buttons, glass, cast-iron cook pots, and other artifacts. "These objects suggest that the lifestyle of the Cherokee on one hand was surprisingly modern and westernized but that they were still very distinctive and native," Riggs said. Links to various resources on the Trail of Tears http://www.nationaltota.org/the-story/

Cherokee Heritage Center www.arch.dcr.state.nc.us/tears/

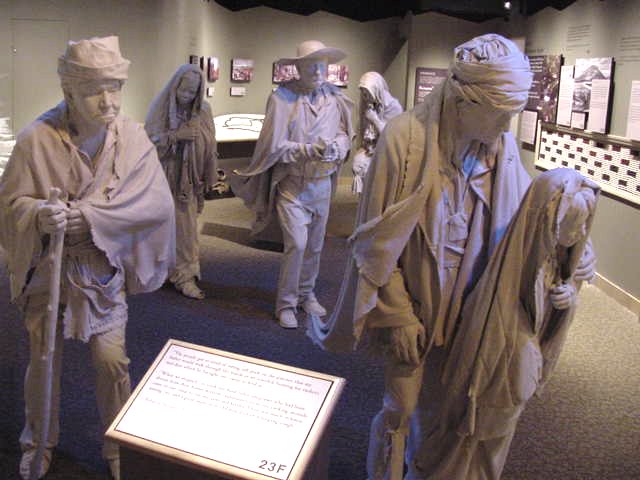

In 1987, the U.S. Congress included about 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) of the Trail of Tears in the National Park Service's National Trails System.

"New World" Film Revives Extinct Native American Tongue In Cherokee Country, Reviving a Tree's Deep Roots America's Lost Colony: Can New Dig Solve Mystery? The Cherokee Trail of Tears - 1838-1839

Trail of Tears Association Tennessee Chapter Trail of Tears Commemorative Ride Trail of Tears: An Infamous Journey to an Unfamiliar Land The Trail of Tears Brief History of The Trail of Tears - Cherokee Messenger Video Cherokee Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy This two-hour documentary explores America's darkest period: President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation to Oklahoma in 1838. Thousands of Cherokees died during the Trail of Tears, nearly a quarter of the Nation. They suffered beyond imagination and when they finally arrived in Indian Territory, they arrived almost without any children and with very few elders, in a way they arrived with no past and no future.

The Cherokee Rose No better symbol exists of the pain and suffering of the Trail Where They Cried than the Cherokee Rose . The mothers of the Cherokee grieved so much that the chiefs prayed for a sign to lift the mother's spirits and give them strength to care for their children. From that day forward, a beautiful new flower, a rose, grew wherever a mother's tear fell to the ground. The rose is white, for the mother's tears. It has a gold center, for the gold taken from the Cherokee lands, and seven leaves on each stem that represent the seven Cherokee clans that made the journey. To this day, the Cherokee Rose prospers along the route of the "Trail of Tears". The Cherokee Rose is now the official flower of the State of Georgia. Knowing that their children might not survive the journey during the Trail of Tears in 1838, the mothers grieved and cried in sorrow. One night the elders prayed for a sign that would lift the mother's spirits and give them strength. The next day a beautiful flower, the Cherokee Rose, began to grown where the tears had fallen. To this day, you can see the wild Cherokee rose growing along the route of the Trial of Tears into eastern Oklahoma. The white color of the rose represents the tears that were shed; the gold center symbolizes the gold taken from Cherokee lands; the seven leaves on each stem stand for the seven Cherokee Clans. Wounded Knee

General Nelson A. Miles, division chief officer, during the Wounded Knee Massacre had this to say:

Sand Creek November 29, 1864

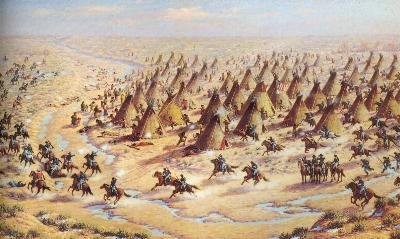

Colorado Territory during the 1850's and 1860's was a place of phenomenal growth spurred by gold and silver rushes. Miners by the tens of thousands had elbowed their way into mineral fields, dislocating and angering the Cheyennes and Arapahos. The Pike's Peak Gold Rush in 1858 brought the the tension to a boiling point. Tribesmen attacked wagon trains, mining camps, and stagecoach lines during the Civil War, when the military garrisons out west were reduced by the war. One white family died within 20 miles of Denver. This outbreak of violence is sometimes referred to as the Cheyenne-Arapaho War or the Colorado War of 1864-65. In the spring of 1864, while the Civil War raged in the east, Chivington launched a campaign of violence against the Cheyenne and their allies, his troops attacking any and all Indians and razing their villages. The Cheyennes, joined by neighboring Arapahos, Sioux, Comanches, and Kiowas in both Colorado and Kansas, went on the defensive warpath. Books Black Kettle : The Cheyenne Chief Who Sought Peace But Found War As white settlers poured into the west during the nineteenth century, many famous Indian chiefs fought to stop them, including Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Geronimo. But one great Cheyenne chief, Black Kettle, understood that the whites could not be stopped. To save his people, he worked unceasingly to establish peace and avoid bloodshed. Yet despite his heroic efforts, the Cheyennes were repeatedly betrayed and would become the victims of two notorious massacres, the second of which cost Black Kettle his life. In this first biography of black Kettle, historian Thom Hatch at last gives us the full story of this illustrious Native American leader, offering an unforgettable portrait of a chief who sought peace but found war.

"At dawn on November 29, 1864, more than seven hundred U.S. volunteer soldiers commanded by Colonel John M. Chivington attacked a village of about 500 Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians along Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado Territory." |

Thanks ©Sparrow for this wonderful feather

Please click on any of the links below to journey around the museum. If you need to get back to the main page at any time just click on Sparrow's feather on any page and you will be transported home.

Exceptional Women Pages

Rest of the site

Ancient Tracks part of the Business

Museum Research & Curator

Gloria Hazell

Site created by Dragonfly Dezignz ©August, 2006