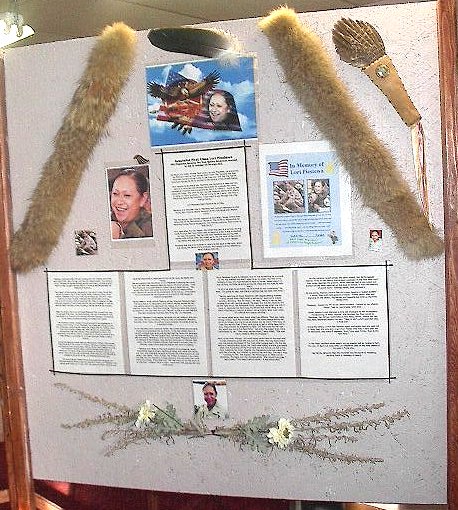

Private First Class Lori Piestewa Private Piestewa became the first Native American woman to die in combat on foreign soil.

On March 23, 2003, Private First Class Lori Ann Piestewa, a Hopi woman from Tuba City, became the first American woman soldier killed in the Iraq war, and the first Native American woman to die in combat in the service of the United States. She and her company were considered MIA. After an attempt to free American prisoners of war it was learned that Lori Piestewa, as well as several other members of her company, did not survive the ambush.

The American Indian College Fund announced it has established a college fund in honor of Lori Piestewa, The scholarship will go toward any remaining unmet financial needs for college that her children have when they become college age, after taking into account other scholarships that have already been established for them. Any remaining funds will be used to underwrite an annual scholarship to a tribal college or university for a female American Indian military veteran. A fund has been set up for the family of Lori Piestewa, During the National Indian Gaming Association's (NIGA) 2003 Annual Trade Show and Convention in Phoenix, Arizona, a moment of silence was observed and prayers were offered, led by Color Guards from the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation and the Oneida Indian Nation of Wisconsin. An honor song was performed by Southern Nation drum group. Over the three-day conference, NIGA received over $85,000 in pledges to be given to the Lori Piestewa Memorial Fund. The Grand Canyon State Games announced the inaugural Lori Piestewa National Native American Games to honor Lori Piestewa. The games were held July 17-20, 2003 throughout northern Arizona and attracted thousands of participants from as far away as Alaska and Hawaii. "We are grateful that the family of Lori Piestewa is allowing her name to be used with the inaugural National Native American games, " said Erik Widmark, executive director Grand Canyon State Games. "We accept this honor with great humility and profound responsibility. Lori's passion for sports will be emblematic of the energy, enthusiasm and commitment the participants will put forth in this inaugural national competition."

Squaw Peak in north-central Phoenix will be renamed Piestewa Peak. The State Board on Geographic and Historic Names waived its five-year waiting period and approved the change by a 5-1 vote before a cheering crowd after a four-hour hearing. The board sided with dozens of supporters who said that the word "Squaw" is offensive and that the mountain should be renamed after Army Pfc. Lori Piestewa, pronounced py-ESS-tuh-wah. The Hopi from Tuba City.

If Lori had been born a century earlier, the United States government would have considered her an enemy. In the late 1800s, the U.S. Cavalry invaded Hopi lands and decreed that the fields now belonged to white settlers. The Hopi fought back, not with guns or arrows, but with nonviolent resistance. (The name Hopi means "Peaceful People.") In defiance of the military, Hopi farmers continued to cultivate their lands. The Army arrested nineteen Hopi leaders and sent them to Alcatraz, where some spent as long as two years in solitary. Piestewa was raised in this Hopi tradition of nonviolence, which emphasizes helping others, starting at home, with one’s own family and clan, and extending outward to include the entire community and nation. (Her father, Terry, is Hopi; her mother is Hispanic.) As a baby, Lori had her hair washed in a Hopi ceremony and was given the name Köcha-Hon-Mana, White Bear Girl. "We Hopi were put on this earth to be peaceful," explains Terry, a short, round man with graying hair and a soft voice. Terry Piestewa fought in Vietnam, but it’s not something he is proud of. He was drafted and didn’t want to go to prison like two of his brothers-in-law who had refused to fight in Korea. Asked about his tour of duty, he folds his arms across his chest and his eyes fill with tears. "A lot of us that did do harm, we have that on our conscience," he says. "It’s going to stay, and there’s nothing that can take that away." Maybe watching all those Westerns with people getting scalped makes people think that’s what a warrior is," says Lori’s oldest brother, Wayland. But for Hopis, he says, being a warrior has nothing to do with hurting people. "My sister is a warrior because she did the right thing, the honorable thing: going to Iraq when she didn’t have to, because she felt it was the ethical and moral thing to do. That’s what being a warrior is about: doing what’s right, even when it’s difficult and means sacrifice." Lori never shied away from doing what was difficult. "She was really strong-willed," says her brother Adam. "We were always telling her not to do things, and she’d just go ahead and do them." The boys of Tuba City learned that if they were going to get in White Bear Girl’s face, they’d better be prepared to fight. Lori was small for her age – she would top out at five foot three – but even the bigger boys were intimidated by her. "She never backed down," says Adam. "She was never afraid to take on anybody." Most of the time, though, Lori used those same traits in the Hopi way: to help whatever group she was part of. When she was eight years old, she played shortstop for the local Little League team. On the day before a championship game, the coach was hitting practice grounders when one ricocheted off the iron-hard dirt and struck Lori full in the face, breaking her nose. Despite two blackened eyes that made her look like a panda, she insisted on playing the next day. The team was counting on her, she argued. Her family gave in. With Lori at shortstop, the team won the championship. "She couldn’t not play," says Adam. This wasn’t about choice – it was about duty. As the vehicles raced across the open desert, the 507th lagged behind. Tires on the heavy trucks spun uselessly in the fine sand until their axles reached the ground. Mired vehicles had to be pulled out; broken trucks were repaired on the spot or towed. It was the essence of grunt work – nothing heroic, just necessary. At one point, Jessica Lynch’s five-ton truck, hauling a "water buffalo" – a trailer filled with 400 gallons of water – broke down. She was standing in the desert, frightened and bewildered, when a Humvee rattled over. Piestewa – known as "Pi" to her fellow soldiers – looked at her shaken friend. "Get in, roommate," she said. When Jessica Lynch thanked a long list of people at her triumphant homecoming in West Virginia, she devoted her final words to Piestewa, her former roommate at Fort Bliss, Texas, where the two had been stationed before the war. "Most of all," Lynch said that day, "I miss Lori." Since the attack, Lynch has insisted again and again that she was not a hero, that she was only a survivor. Asked who was a hero that day in Nasiriyah, she doesn’t hesitate. "Lori," she says firmly. "Lori is the real hero."

|

Thanks ©Sparrow for this wonderful feather

Please click on any of the links below to journey around the museum. If you need to get back to the main page at any time just click on Sparrow's feather on any page and you will be transported home.

Exceptional Women Pages

|

|

|||||

Rest of the site

Ancient Tracks part of the Business

Museum Research & Curator

Gloria Hazell

Site created by Dragonfly Dezignz ©August, 2006