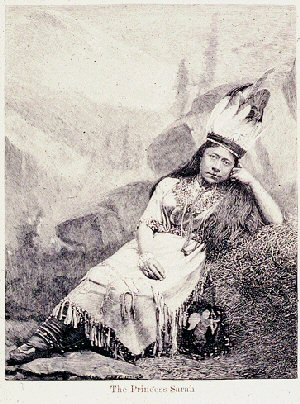

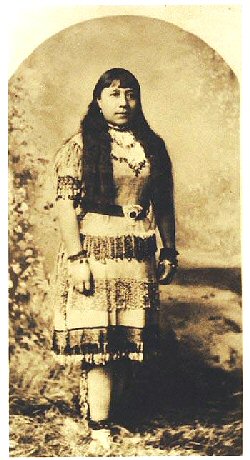

Sarah Winnemucca ( Thocmetony) "I was born somewhere near 1844, but am not sure of the precise time. I was a very small child when the first white people came into our country. They came like a lion, yes, like a roaring lion, and have continued so ever since, and I have never forgotten their first coming. My people were scattered at that time over nearly all the territory now known as Nevada. My grandfather was chief of the entire Piute nation, and was camped near Humboldt Lake, with a small portion of his tribe, when a party travelling eastward from California was seen coming. When the news was brought to my grandfather, he asked what they looked like? When told that they had hair on their faces, and were white, he jumped up and clasped his hands together and cried aloud--"My white brothers--my long-looked for white brothers have come at last!""

Born in 1844 the daughter of Poito (Chief Winnemucca or Old Winnemucca) and Tuboitonie at Humboldt Sink, Nevada (then claimed by México as part of Territorio de Alta, California). Her maternal grandfather was Captain Truckee “Good,” a Winnemucca Northern Paiute chief who fought with John C. Frémont during the Mexican-American war. Although Sarah claimed that her father was chief of all the Northern Paiute (and she was therefore often called the "Paiute Princess" by the press), the Paiute had no centralized leadership and her father, though influential, was the leader of a small band. At the time of Sarah's birth, Northern Paiutes and Washos were the sole inhabitants of the land that is now western Nevada. Her birth coincided with the beginning of an era of dramatic historical changes for her people, changes in which she would, as an adult, play an important and often thankless role. Her grandfather, Chief Truckee, welcomed the arrival of his "white brothers" and helped General John C. Fremont in the Bear War against Mexican control of California. However, her father, Chief Winnemucca, did not trust the white people and cautioned his own people to keep their distance. Perhaps hearing these opposite viewpoints became a portent of her life, which was spent attempting to interpret the two cultures to each other. She worked throughout her life to communicate between her people and the white people, to defend Paiute rights, and to create understanding.

Sarah was first introduced to white people at age six when her grandfather insisted she go with him to California. She was initially frightened, but did like such luxuries as beds, chairs, brightly colored dishes and the food she was served. For a time, Winnemucca lived a peaceful life, but then ranchers tried to assault her older sister. Winnemucca's family decided to move back to Nevada hoping for a peaceful life, but their territory had been invaded by more and more white settlers. Winnemucca's father took her and other relatives to Virginia City to seek help. He went onstage to ask people for their help in understanding how Indians live and how they were being pushed off their land by thoughtless settlers. Winnemucca translated her father's words into English. From that time on, she became a spokesperson and activist for Indian rights. When she was thirteen, her grandfather had arranged for Sarah and her sister to become members of Major Ormsby's household at Mormon Station, now Genoa, Nevada. By the time she was fourteen, she had acquired five languages, three Indian dialects, English and Spanish. Both times that she left her tribe, Sarah returned following an incident of white people treating her tribe poorly. Sarah's final visit in the white culture at age sixteen fulfilled her grandfather's deathbed request that she and her sister Elma be educated in a convent school at San Jose, California. The two girls were never officially admitted to the school, but during their few weeks there, she continued to acquire more knowledge and experience in the new culture. As a child she was given the northern Paiute name Thocmetony, which means "shell flower" and wrote the following about that name:

She travelled without sleep over 200 miles in 48 hours over treacherous Idaho terrain. She freed her father and other captives and served as an army scout in the war against the Bannocks. She then spoke out, describing the plight of her people, exiled from their homelands, and the treachery of dishonest Indian agents. She drew much attention, and was able to speak with President Rutherford Hayes and Interior Secretary Carl Schurz; Sarah did receive promises of improvements for her people, which were later broken by the government, promises to return her tribe to the Malheur Reservation were never honored. Despite passage of Congressional legislation enabling the return of the Paiute land, the legislation was never enacted. Even though she worked tirelessly for her people, the broken promises caused them to distrust her. Still, she dedicated the remainder of her life to her work, giving more than 400 speeches to gain support for the Paiutes. Many of her speeches were given on the East Coast through the support of Elizabeth Peabody and Mary Peabody Mann. Her lectures helped increase awareness and sympathy for the plight of Native Americans. With encouragement of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Massachusetts senator Henry Dawes, and Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, she wrote an autobiography, 'Life Among the Piutes[sic]: Their Wrongs and Claims'. It was the first book written in English by a Native American woman. Although Sarah was a better public speaker than writer, the words are still forceful and are more readable than the stilted prose then popular in the Victorian era. While lecturing in San Francisco, California, Sarah met and married Lewis H. Hopkins, an Indian Department employee. It is said that she was also married to Lt. E. C. Bartlett but left him within a year because of his intemperance. She later married an Indian husband, but left him for his gross abuse of her. Sarah was dedicated to teaching school to Paiute children and opened a non-government school for Indian children which was to promote the Indian lifestyle and language, called "Peabody's Institute" near Lovelock, Nevada. She used her royalties from her book and donations. However, she ran out of money and was never able to get Federal funding. The school operated briefly, until the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 required Indian children to attend English-speaking boarding schools. Despite a bequest from Mary Peabody Mann and efforts to turn the school into a technical training center, Sarah's funds were depleted by the time her husband died of tuberculosis. His disease and gambling left her with little money and so the school was closed. Sick herself, Sarah moved to live with her sister Elma and she spent the last four years of her life retired from public activity. Sarah died in October 1891 at her sister’s home near Henry’s Lake, Idaho. "Sarah Winnemucca will always be remembered as a dedicated Native American woman who belonged to two cultures. With one foot in the Indian Nation and the other in the white man's world, she sped across the plains like a blazing arrow only to fall short of her target. Although the Princess was recognized throughout the land as the passionate voice of the Paiute Indians, she was treated with indifference by the United States Government. Disillusioned and betrayed, Sarah died before she completed her, mission, believing herself to be a failure"

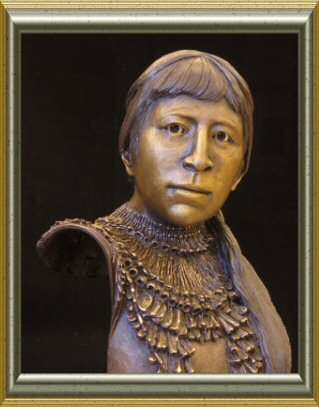

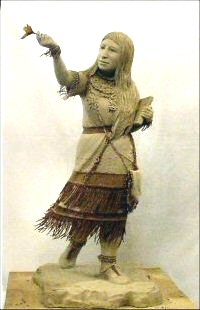

The Sarah Winnemucca Statue Sarah Winnemucca brings descendant and artist together for sculpture and Nevada Day parade

One hundred-thirteen years after her death, Paiute activist Sarah Winnemucca recently crossed the paths of two people laboring to portray her.

In 2005 Sarah Winnemucca was honored with a statue in the U.S Capitol. Each state sends two statues to the Capitol, and Nevada choose her to represent their state in 2005.

Dorothy Ely says she is afraid of the airplane ride to Washington, D.C., but still could not miss seeing the statue of her great-aunt, Sarah Winnemucca, placed in National Statuary Hall. “I think it’s great and I want to be there,” said Ely, 69. “It’s very moving.” She is not alone. Many, including 26-year-old sculptor Benjamin Victor, are excited that the effort to make Winnemucca the second statue from Nevada to sit in the Capitol is almost accomplished. Today, there will be a dedication of a statue depicting Sarah, the daughter of Chief Winnemucca, who fought for equal rights for her people. “I can’t wait,” said Victor, of Aberdeen, S.D. “I’ve never even been to D.C. and to go for something like this — I’m a bit starstruck.” A year out of college, Victor’s first commission will be alongside works by the master sculptors he studied. He says he feels like the kid who dreams of meeting basketball great Michael Jordan and finally gets to look up at him in awe. “It’s your greatest feeling,” he said. “The piece itself is more deserving than I am.” Carrie Townley Porter, who proposed the idea to the Nevada Women’s History Project five years ago and was part of the selection committee, said Nevadans will be proud when they travel east and see Winnemucca. “Putting Sarah back in Washington to be a light for Americans will be the greatest history accomplishment of my life,” she said. The endeavor, from drafting the bill and getting it passed by the state Legislature to raising the necessary funds, was not easy, she said “We worked hard to get the bill passed and we did,” Porter said. Former Assemblywoman Marcia de Braga sponsored the bill, which was signed by Gov. Kenny Guinn on May 29, 2001. Initially, $100,000 was attached to the bill to pay for the statue. “However, that year there was a tight budget,” de Braga said. “So I removed the money. I just wanted the bill regardless and hoped we could find a way to raise the money.” There were some who questioned why Winnemucca was chosen, instead of another political figure. “It was hard to argue the fact that Sarah Winnemucca accomplished so much,” de Braga said. “She was picked not as a Native American but because she was Nevada’s first public woman.” Winnemucca lectured to whites at home and across the country seeking justice for the Paiute people. In 1880, she met with President Rutherford B. Hayes and other officials in Washington, D.C., about the poor conditions of her people. “Sarah’s weapon was her eloquent tongue,” said Sally Zanjani in her biography “Sarah Winnemucca.” With the bill passed, the next challenge was to raise money. There never should have been opposition to the statue but there was, De Braga said. “There was some controversy among Native Americans,” she said. The book says some people did not like the fact that Winnemucca married white men and called her an “assimilationist.” “Some see her as a “traitor” who sold out her people during the Bannock War and even cost Paiute lives,” Zanjani said in her book. However, Zanjani said that conclusion did not hold up. And the controversy did not stop the Nevada Women’s History Project from going around the state to raise money. “We envisioned that this should be a citizens’ project, ” Porter said. “We wanted people to have a sense of ownership in that statue that represents Nevada. That they helped put that statue there.”

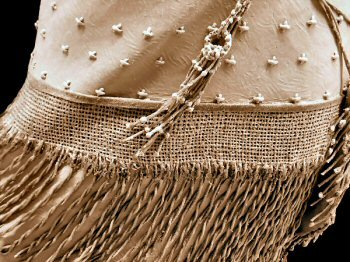

One of the first donations came from an elementary school in Schurz, which Porter said held a read-a-thon and raised $26. The Sarah Winnemucca Elementary School in Reno collected $700, Porter said. “And we were told the smallest donation was one cent,” she said. Then Nevada first lady Dema Guinn, who was part of the selection committee, stepped in and helped raised money not only for the statue in Washington but enough to have a full-size statue in Carson City. “I did go after some people that I encouraged to give some money,” Guinn said. “This is such an important thing. This is about history. This is about what Nevada is all about.” Winnemucca is the fourth woman to be placed in the hall, which Guinn said makes this an extra-special honor for Nevada. “We had strong women and she was one of them,” Guinn said. “Her drive and dedication to me, I just marvel at that.” She said she also marveled at Victor’s ability to capture the essence of Winnemucca. “I think people will walk in and their eye will go straight to Sarah,” Guinn said. Victor agrees. The proclaimed perfectionist, who spent almost four months at a foundry in Colorado with his statue making sure every step of the process went flawlessly, proudly says Winnemucca will stand out from every other statue in the hall. He was there bending the fringes on the bottom of her dress to look windswept. Even the warm-brown patina finish had to hit the light just so. Victor, who will be the hall’s youngest sculptor, says the other statues are static. “Sarah is in motion. And that will set her apart from every sculpture in the hall,” he said. “I think everyone when they see it is going to be surprised and happy with it.” The statue of Winnemucca had to be in motion to depict her life as an activist and the enthusiasm she had, Victor said. The irony is that Winnemucca now will stand permanently where she begged for, but was denied, help for her Pyramid Lake tribe. “She believed she was a failure when she died,” Victor said. “She died believing she had failed in her causes. Here we are 100 years later realizing she is their equal.” Although it will be sad to say goodbye to the woman he has spent the past year with, Victor says he wouldn’t want to keep her. “She needs to be out there in D.C. where she always traveled,” he said. “She was there in her lifetime trying to make a difference. And she will be making a difference forever in the Capitol. That’s pretty cool.”

Books

Life Among the Piutes[sic]: Their Wrongs and Claims, published in 1883. Life Among the Piutes is Sarah Winnemucca's powerful legacy to both cultures, the Native Americans and the whites. It appeared in 1883, the first book ever published that was written by a Native American woman. Following the oral tradition of her people, she reaches out to readers with a deeply personal appeal for understanding, recording a portion of the history of the far west from the Native American perspective. The book was a monumental achievement, recording the Native American viewpoint of whites settling the west, told in a language that was not her own and written and published by a woman during the time when even white women were not allowed to vote, second only to the work she performed every day to promote understanding across cultures. Posthumously, she was awarded the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame Award for her book from the Friends of the Library, University of Nevada, Reno. In 1994 an elementary school in Washoe County School District was named in her honor, Sarah Winnemucca Elementary.

"The women sit behind [the men] in another circle, and if the children wish to hear they can be there too. The women know as much as the men do, and their advice is often asked. We have a republic as well as you. The council-tent is our Congress and anybody can speak who has anything to say, women and all. If women could go into your Congress I think justice would soon be done to the Indians." Sarah Winnemucca

The Governor of Nevada proclaimed April 6th, 2005 as Sarah Winnemucca Day. Please click HERE to see the proclamation

Thanks to the following people for their input

Converted to HTML by Dan Anderson, December 2005. These files may be used for any non-commercial purpose, provided this notice is left intact. —Dan Anderson, www.yosemite.ca.us

|

Thanks ©Sparrow for this wonderful feather

Please click on any of the links below to journey around the museum. If you need to get back to the main page at any time just click on Sparrow's feather on any page and you will be transported home.

Exceptional Women Pages

Rest of the site

Ancient Tracks part of the Business

Museum Research & Curator

Gloria Hazell

Site created by Dragonfly Dezignz ©August, 2006